|

We had no idea.

For two years, scores of fellow students and dozens of faculty and staff – including those of us in the alumni and foundation offices – knew Jessica Goodell. At least, we had made her acquaintance.

Some worked with her on class projects. Others saw her at campus events as a student ambassador. But none of us understood who this remarkable woman in our midst was or what she had experienced. We also had no clue of the devastating affects those experiences had – and some days, were still having – on her.

That’s just the way she wanted it, because she wasn’t ready to talk about it yet. She didn’t want people to look at her differently.

She didn’t want the questions. She was doing her best to fit in – to return to a “normal” life. So she kept it all a secret. Until now.

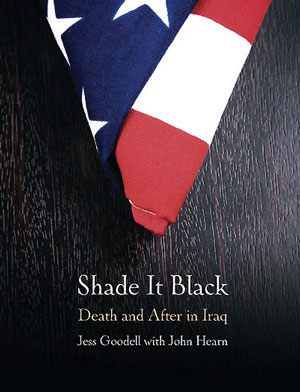

In 2010, Ms. Goodell graduated from SUNY Fredonia with a degree in psychology and a minor in philosophy. Less than a year later, she has published a book, Shade it Black: Death and After in Iraq, detailing her experiences during and following her enlistment in the United States Marine Corps, as part of the Mortuary Affairs Unit in Iraq. Her job was to “process” dead marines.

Lance Corporal Goodell’s path to the Middle East was fairly unlikely, almost accidental. In 2001, she was preparing to graduate from Bemus Point/Maple Grove High School, in a quaint little resort town on Chautauqua Lake. She was, of course, going to college. After all, she was sixth in her class, had played varsity basketball since ninth grade, and was a saxophonist in the jazz and concert bands. She had lived a safe, almost pristine existence seemingly as far away as possible from the place she would soon find herself. Yet, shortly before graduation – and despite having paid her deposit at a college and even gone through its orientation program – Jessica joined the Marines. She did so impulsively, she admits, almost in response to a dare of sorts, following a comment made by a recruiter who visited her high school to speak with some young men. Some “tough men.”

“What about tough women?” she asked.

So the recruiter invited Jessica down to his office and showed her a book of all the possible jobs Marines could have. But the one she wanted, joining a tank crew – the one that looked the toughest – wasn’t open to her, because she was a female.

“It was sort of a rebellious act,” she says. “My ego took over. “It just provoked me, and so I said, ‘I’m going to pick the most masculine job in this book, and I’m joining the Marine Corps.’”

She did it on the spot. No consultation with mom and dad. No advice from friends. She just took the challenge, no questions asked.

“I called my parents from a pay phone to tell them about it,” she recalls. “I knew I couldn’t do it face-to-face. When I told them, there was just silence. Stunned silence.”

Joining the Marines was hard enough, but she soon found being a female was extra challenging. Not only did she have to do all of the physical activity, but she also had to contend with a rather hostile attitude toward female Marines – “Marine-ettes” as they are derisively called by some – which made her all the more determined to prove her worth. She would get so frustrated, not just at the males who would make offensive jokes or remarks, hit on her, or assume that she couldn’t hack it. But she would get just as upset at her fellow females who would falter, give in to a sexual advance, or not carry their own weight.

“We were on a run one day, and a female [got tired and] dropped back out of the formation,” Goodell explains. “I looked back, and a male was back there carrying her pack for her. I know it sounds awful, but I was like, ‘What are you doing to me? I’m trying so hard, and you’re falling out of this formation, and it’s making me look bad.’ We (females) were all under the spotlight, and when one of us failed, it looked bad for all the women.”

She was soon sent and completed a deployment to Okinawa, Japan, where she served as a heavy equipment mechanic, but she felt an obligation to also serve in the Middle East. “I just felt like I wouldn’t be a true Marine if I didn’t go to Iraq,” she explained.

However, there were no openings for mechanics at the time, so, in 2004, she volunteered for the Mortuary Affairs Unit – a decision, she admits, she didn’t understand the severity of at the time.

Her platoon was charged with the gruesome job of retrieving deceased Marines from battle zones, roadside bombing sites and other locations, and because of the nature of modern warfare, that was often a deeply disturbing task. She literally saw it all. The worst you can imagine.

In today’s combat, “clean” deaths have gone the way of the Kentucky Long Rifle, replaced by IEDs (Improvised Explosive Devices), discharged at a “safe” distance from their operator, leaving their victims with no warning or hope of survival.

And it was her job to gather those remains – scooping them up with her hazmat-covered hands, if necessary – and bring them back to the base. She was instructed to gather as much as possible, leaving nothing for the insurgents to claim as a trophy, and run through the streets with in victory, as they did to four American civilian contractors earlier in the war.

That was only half of her job. Once back at camp, her team had to catalog the deceased, which often meant trying to discern which remains went with which Marine if multiple deaths occurred. Each victim was chronicled on a form that included a human outline; they were instructed to shade in any parts that were missing, thus, the “inspiration” for the name of her book. And, as dreadful as the visuals were, the smells were even worse. They permeated her clothes. Eating became a terrible challenge, and other Marines usually kept their distance. It became a very lonely existence.

By the time her eight months in Iraq were complete, she lost track of how many bodies she processed. “We were just on survival mode. I’m not sure how many altogether. As many as eight in a day, then nothing for a day or a week, then six…”

Surprisingly, she never processed a female. “We were there for eight months, and not one came through. I think it would have been very hard. I was always sort of dreading it. We had all discussed that, if we had any females come in, I and the other female on our team would process her. But it never happened.”

Her time immediately following her active duty was especially hard on her, as she struggled to adjust back to civilian life and with the very real effects of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which one in four soldiers involved in military combat will experience. War’s awful truth, she had learned, contains none of the honor and romance that movies or video games have tried to sell us for decades.

Video games, in particular, are a flashpoint for Jessica, who watched and overheard fellow students play games with current war-based themes. She gets visibly pained, astonished that people in our country can find fun in it.

“It just hurts. It hurts so badly,” she says. “A lot of the Marines played them too. Because of my unique job…it just hurts to see our culture, or any culture, find entertainment in war. It shows just how far removed we are from what’s going on in the world, how we can make money off of it (games).”

She bounced around to several cities… St. Louis, Seattle, Tucson… before returning to the familiarity of Western New York to attempt to refocus and move on with life.

She completed her associate’s degree at Jamestown Community College (JCC) in just two semesters by carrying course loads of up to 24 credit hours (she had earned some college credits in high school). She graduated in the top of her class and received the top Social Sciences Award, having begun to realize her personal link to the field of psychology and the possibility that it may not only help her find her own answers, but one day she might help others in similar situations.

While at JCC she met John Hearn, a sociology professor from whom she learned a great deal. After graduating, she told him her story, and he suggested that she write it all down, in a journal of sorts, in hopes that expressing it might help her overcome some of the anxiety she was experiencing. He even offered to help her with it. That journal eventually became her book.

She transferred to Fredonia, and decided she wanted to really immerse herself in campus life. She joined Tau Sigma, the honor society for transfer students, as well as Psi Chi, the equivalent for psychology majors. She was inducted into the Golden Key International Honour Society, and began working for the Office of Alumni Affairs as a student ambassador. She did it all, she says with hindsight, to help her fit in and to distance herself from her past.

“I was just really struggling with civilian life,” she recalls. “It was very different, going from a Marine Corps mentality where everything is focused on a group, to a college mentality where everyone seemed focused on themselves. I was only about five years older than most of my peers, but [tuition] was coming out of my pocket, and I had a greater appreciation for the time in the classroom. It was so frustrating to see students paw through their cell phones and show such disrespect for the professors, and for each other. I really struggled with people not turning in their assignments. I would think, ‘Why didn’t you just stay up later, or get up earlier?’”

One person who helped her with that adjustment, and to better understand and process her situation, was Dr. Suthakaran Veerasamy of the Department of Psychology. “He’s a really good professor. When you walk out of one of his classes, it’s like getting out of a group counseling session,” she says. “And I was lucky enough to be on a research team with him. He was really the one who introduced me to this idea of challenging myself – not physically, but my beliefs… things that I thought I knew.”

It’s not surprising that such an approach to healing would appeal to Jessica, because she’s been challenging herself as far back as she can remember. In fact, that’s really “the kicker” in all of this. She never had to do any of this, at least from a financial perspective. She is the daughter of Andy Goodell, currently a New York State Assemblyman, a former Chautauqua County Executive, and a successful attorney.

For a long time, she thought she would just follow in his footsteps and join her father’s practice upon graduation. She also has a pretty well-known cousin – Roger Goodell, the commissioner of the National Football League and a high-ranking NFL executive at the time of her enlistment. She could have used those family connections to her advantage. But she chose to do this, to test and challenge herself – and to an extent, the military system. That challenge, some days, was too much to handle. But now, seven years later, she has gained a better perspective and realizes she performed a valuable and much-needed service to her country.

“One part of me likes to take pride that I was able to do it, that I stuck it out, I didn’t leave

the platoon,” she says. “But the other side of me says, ‘Oh, God, what was I doing…’”

Less than a year after earning her Fredonia diploma, Jessica can only smile as her life has taken one more whirlwind turn. With the book’s release has come a slew of media attention, including interviews with CNN, the BBC, Radio Europe and National Public Radio. She hopes to wrap up her media engagements by late August, when she’ll begin a Ph.D. program in counseling psychology at the University of Buffalo, as she sets out to become a professional psychologist who specializes in assisting veterans.

In the postscript of her story, Hearn tells of a conversation he had with Jessica. In it, she says that if she had a son who wanted to be a Marine she would be O.K. with it, but if she had a daughter, she would not. Two years and some soul searching later, however, she has changed her mind.

“Now, I would not let my son join either,” she admits. “The concept of war and killing others… I just wouldn’t want any child of mine exposed to that. You take that with you forever.”